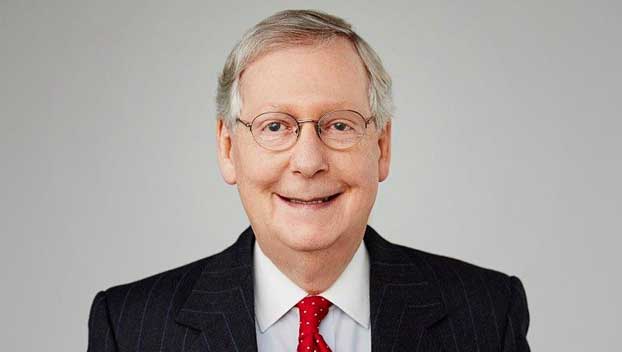

McConnell said he will vote to acquit Trump, sources say

Published 11:30 am Saturday, February 13, 2021

Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell told colleagues Saturday that he will vote to acquit Donald Trump in his impeachment trial, ending the suspense over what the chamber’s most influential Republican would decide and likely slamming the door on chances that the former president would be found guilty.

The longest-serving GOP Senate leader in history made his views known in a letter to fellow Republican lawmakers, according to two sources familiar with McConnell’s thinking who spoke on condition of anonymity to discuss his decision.

Word of McConnell’s decision came minutes before the beginning of Saturday’s session of the Senate trial, which had been expected to be the final day of the proceedings. But lawmakers abruptly voted to open the door to calling witnesses to testify, leaving the trial’s duration uncertain.

Trump is charged with inciting the deadly Jan. 6 riot by his supporters at the Capitol as Congress was formally certifying his election defeat by Joe Biden.

McConnell’s views carry sway among GOP senators, and his decision on Trump is likely to influence others weighing their votes. Seventeen Republicans would need to join all 50 Democrats to reach the two-thirds threshold needed to convict Trump, a margin that seems all but insurmountable.

Many had expected the Kentucky senator to vote to clear Trump of the charges, based on McConnell’s history as a GOP loyalist who likes to take few major risks. But before Saturday, McConnell had said little in public or private about his mindset, and no one was certain what he would decide.

McConnell jarred the political world just minutes after the Democratic-led House impeached Trump on Jan. 13, writing to his GOP colleagues that he had “not made a final decision” about how he would vote at the Senate trial.

It was an eye-opening departure from his quick opposition when the House impeached Trump in December 2019 for trying to force Ukraine to send the then-president political dirt on campaign rival Joe Biden and other Democrats.

McConnell had also told associates he thought Trump perpetrated impeachable offenses and saw the moment as a chance to distance the GOP from the damage the tumultuous Trump could inflict on it, a Republican strategist told The Associated Press at the time, speaking on condition of anonymity to describe private conversations.

But since this week’s trial began, McConnell has voted with a majority of Republicans against proceeding with the trial at all on the grounds that Trump was no longer president.

McConnell’s decision to acquit Trump leaves the party locked in its struggle to define itself in the post-Trump presidency. Numerous and fiercely loyal pro-Trump Republicans and more traditional Republicans who believe the former president is damaging the party’s national appeal are struggling to decide the GOP’s direction.

A guilty vote by McConnell would have likely done even more to roil GOP waters by signaling an attempt by the party’s most powerful Washington leader to yank the party away from a figure still revered by most of its voters.

“The overwhelming number of Republican voters don’t want Trump convicted, so that means any political leader has to tread carefully,” said John Feehery, a former top congressional GOP aide. While Feehery noted that McConnell was clearly outraged over the attack, he said the senator is “trying to keep his party together.”

Over 36 years in the Senate, the measured McConnell has earned a reputation for inexpressiveness in the service of caution. The suspense over how he was going to vote underscored how much is at stake for McConnell and his party.

McConnell has spent the trial’s first week in his seat in the Senate chamber, staring straight ahead.

A guilty vote by McConnell would have enraged many of the 74 million voters who backed Trump in November, a record for a GOP presidential candidate. That could expose Republican senators seeking reelection in 2022 to primaries from conservatives seeking revenge, potentially giving the GOP less appealing general election candidates as they try winning Senate control.

McConnell’s decision will no doubt color his legacy. He turns 79 next Saturday and doesn’t face reelection for almost six years. Even critics say McConnell likes to play the long game.

“For McConnell, it’s always strategy, it’s always about how he can live to fight another day,” said Colmon Elridge, chair of the Kentucky Democratic Party.

McConnell maneuvered through Trump’s four years in office like a captain steering a ship through a rocky strait on stormy seas. Battered at times by vindictive presidential tweets, McConnell made a habit of saying nothing about many of Trump’s outrageous comments. He ended up guiding the Senate to victories such as the 2017 tax cuts and the confirmations of three Supreme Court justices and more than 200 other federal judges.

Their relationship plummeted after Trump’s denial of his Nov. 3 defeat and relentless efforts to reverse the voters’ verdict with his baseless claims that Democrats fraudulently stole the election.

It withered completely last month, after Republicans lost Senate control with two Georgia runoff defeats they blamed on Trump, and the savage attack on the Capitol by Trump supporters. The day of the riot, McConnell railed against “thugs, mobs, or threats” and described the attack as “this failed insurrection.”

A week later, the Democratic-controlled House impeached Trump for inciting insurrection. Six days after that, McConnell said, “The mob was fed lies” and he added, “They were provoked by the president and other powerful people.”