Road to Recovery: Hopkins County recovery leaders ‘still making big decisions’

Published 4:42 pm Friday, October 27, 2023

This is part four of a five-part series – Road to Recovery – looking into the state of recovery from 2021 tornadoes in Western Kentucky and 2022 floods in eastern Kentucky, with a focus on what each region needs from its political leaders.

On Dec. 10, 2021, Hopkins County Judge-Executive Jack Whitfield had about three days left in his COVID quarantine.

But when tornadoes struck that night in Western Kentucky, isolation was immediately out of the question. Whitfield knew he had to do something.

He ended up doing what felt like “everything.”

The morning after the tornadoes, Whitfield made a plan to drive to Dawson Springs to help search and rescue crews look for survivors amid destroyed homes.

“As soon as I stepped out of the truck, I couldn’t go a foot before I had people asking me, ‘What do we do here?’ ‘What do we do there?’ ” he said.

“I’ve never worked in emergency management – I’ve been a coal miner most of my life. So I began making decisions immediately that I had no experience with, but somebody had to.”

Hopkins County Judge Executive Jack Whitfield and Long Term Recovery Group Co-Chair Heath Duncan pose in front of county maps in Madisonville, Kentucky.

Late Friday that Dec. 10, a tornado ran through 11 counties: Fulton, Hickman, Graves, Marshall, Lyon, Caldwell, Hopkins, Muhlenberg, Ohio, Breckenridge and Grayson.

According to the National Weather Service, its 165.7-mile path was the longest in U.S. history. Eighty-one Kentuckians died from the storm and its aftermath. Over 600 were injured.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency estimated that 257 homes were destroyed, and over 1,000 otherwise damaged.

Whitfield said that the 48 hours after the tornado were easily the worst of his life. Witnessing destroyed homes and businesses, people screaming and crying trying to get people out, tornado victims laid out at the volunteer fire department’s temporary morgue– it was devastating, he said.

He received so many calls that his recent call log only went back one or two hours. Whitfield realized then that he could not do it alone; he needed to delegate. So he assembled a team, and after six full sweeps of search and recovery, the cleanup effort began.

Whitfield was told that cleanup would cost $50 million, money Hopkins County did not have. His team got to work anyway.

They cleared roads to shut off busted gas, water, sewer and electric utilities to avoid explosions or fires from ruptured lines.

Groups of volunteers began pushing debris from people’s yards into the road, because FEMA does not clean up debris on private property. That alone saved the county about $14 million, money now going into the rebuild, Whitfield said.

Whitfield scheduled the inundation of volunteers weeks and months out, because there was not enough housing to go around in the immediate aftermath.

It took a month before he felt like he could take a breath.

‘Still making big decisions’

Nearly two years after the tornadoes, Heath Duncan still finds himself driving home from Dawson Springs at 8:30 p.m. after Hopkins County Long Term Recovery Group meetings.

Duncan, the group’s co-chair, said that the recovery effort is “still very much alive.”

“We’re still making big decisions,” he said.

The LTRG coordinates the recovery effort, by corralling all the region’s nonprofits and accessing money from different funding sources, Duncan said. So far they’ve leveraged nearly a million dollars.

Recovery includes case management, Duncan said. The LRTG partnered with professionals who met with every family and survivor to determine their needs, from mental health help to a house to a new roof or porch.

Originally, nearly 2,000 people needed some sort of assistance. In early October, the case managers reported only 22 remaining open cases.

They’ve accessed funds for mental health awareness, including starting a day camp for kids with disaster trauma-based curriculum and bringing mental health counselors into schools.

They’ve built more resilient homes with fortified roofs, storm shelters and occasionally, third front doors to make residents feel more secure.

United Way built a donation warehouse to house perishables in case of a future disaster.

“We’ve touched nearly everyone in some way, everyone that was affected, and met many if not all of those needs,” Duncan said. “So that’s something we’re pretty proud of. Last night, it was kind of a monumental time for us.”

Housing: A long ways to go

Duncan said about 600 homes needed to be rebuilt after the tornado, and nonprofits have built a combined 75 to 80 homes, in addition to private builds.

There was a housing crisis before the tornadoes, Whitfield added. Both expect full housing recovery to take upwards of a decade.

But Whitfield doesn’t think they will ever replace the total number of houses lost.

Some destroyed older homes were on smaller lots that could not be built on today, due to updated planning and zoning ordinances.

Plus, the property value of the houses being built by some of the nonprofits are higher than the original homes, meaning it will take less houses to rebuild the pre-tornado tax base.

Getting low-income renters into affordable housing has been one of the biggest struggles, Duncan said.

Nonprofits can’t build apartments for landlords to then make a profit from, and landlords who decide to rebuild are not incentivized to charge the same rent.

Consequently, many former renters have been priced out of Hopkins County, and will likely not return.

It’s not all negative, Whitfield said. A silver lining of the tornado taking most of Dawson Spring’s older housing is that now they can start over with nicer, new homes.

“Hopefully with the rebirth and being basically a new city, that will encourage others to come in and expand outside of the boundaries where the houses were,” Whitfield said.

Economy

Before the tornadoes, the Madisonville-Hopkins County Economic Development Corporation was close to a deal. A company was planning on buying a spec building that had sat in Dawson Springs for 15 years. The move would have created 100 jobs, making the company the area’s number one or two employer, behind only the school system.

But, instead of closing the deal in January 2022, the building got blown away in a tornado.

“The economy in the areas that were most affected by the tornado wasn’t great before, and it’s a little worse now,” Whitfield said. “But again, I see it as an opportunity to be better than we were.”

He added that they were trying to locate some industries on economic development property in Dawson Springs, and expected a major announcement soon.

“If we can get some of those things done, get some apartments that would be affordable and jobs in the area, that would be a huge step in recovery,” he said.

“But it’s taken a lot longer than I want it to, and no guarantees yet.”

‘Chaotic, at best’

FEMA has denied every single request for reimbursement for roads damaged in the tornadoes, Whitfield said. They didn’t have enough evidence of what shape the roads were in before the storm.

“So I don’t know if we’re supposed to say, ‘Hey, there’s a tornado. Come on. Let’s run in front of it with a camera so we can see what kind of shape the roads are in and then we’ll do it again after,’ “ Whitfield said.

Working with FEMA has been “chaotic, at best,” he said.

Gov. Andy Beshear was “exceptional” in getting them help, and their state representatives have also “gone to bat for us,” Whitfield said.

But help dealing with federal funding entities, like FEMA, has been one of their needs.

“I don’t know that there’s a whole lot left from the state that we are going to ask for,” Whitfield said. “Maybe some additional funding to help build some houses, but there’s not a whole lot I think they’ll need to do.”

‘You can’t hide from anything’

At the Dawson Springs public library, there is a photo album of the tornado aftermath. One photo depicts a completely destroyed home at 604 E. Keigan Street.

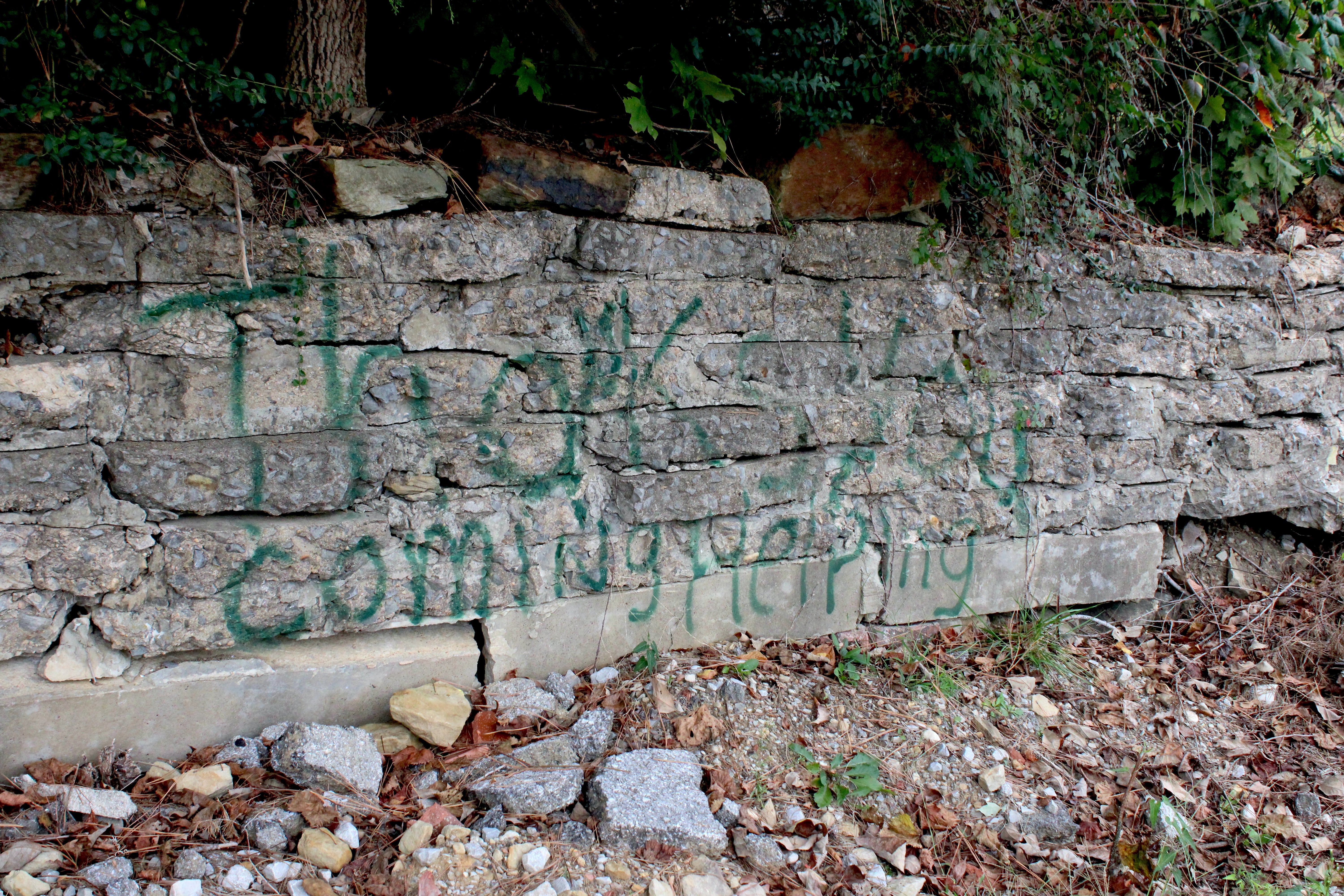

Nearly two years later, 604 E. Keigan is home to an elaborate Halloween display, fake gravestones and all. In fact, Dawson Springs’ streets are lined with decorations – signs of resilience, of life moving on.

Dawson Springs resident Crystal Day said that when you experience a loss like they did, the community gains a “togetherness.”

“Total strangers came from not only just around our area, but people from other countries came here,” she said. “… Seeing stuff like that gave me a lot of hope, and I think that’s the reason why so many people are building back now because it did strengthen our community.”

While physical recovery feels close, Day said she doesn’t think people will ever emotionally recover. She’s grateful for the political attention the community received.

“We saw Gov. Beshear here a lot,” she said. “I mean, we literally saw the man walking up and down the streets of Dawson Springs multiple times.”

Judith DeLong came home to Dawson Springs when her grandson called her after the tornado. In October, she was building a garden for a new Habitat for Humanity house.

She said that the community has changed for the better, by opening people’s eyes to appreciate things more.

But people are still scared, she said. They want more shelters.

Duncan said that Hopkins County is entering a new phase of recovery; for the first time, they’re not sure if they will need volunteers this time next year.

Whitfield said that no matter how many times they go through something like this, they can never be fully prepared.

“You can’t hide from anything,” DeLong said.

Dawson Springs, a town in West Kentucky’s Hopkins County, was hit hard by the 2021 tornadoes. It destroyed 65 to 70% of homes and buildings, killing 14 people.

Dawson Springs, a town in West Kentucky’s Hopkins County, was hit hard by the 2021 tornadoes. It destroyed 65 to 70% of homes and buildings, killing 14 people.

Teams of nonprofit volunteers visit Dawson Springs for continued recovery work.

Dawson Springs, a town in West Kentucky’s Hopkins County, was hit hard by the 2021 tornadoes. It destroyed 65 to 70% of homes and buildings, killing 14 people.

A spray painted message in a Dawson Springs neighborhood thanks volunteers for coming to help the town recover from the tornadoes.

Teams of nonprofit volunteers visit Dawson Springs for continued recovery work.

Dawson Springs, a town in West Kentucky’s Hopkins County, was hit hard by the 2021 tornadoes. It destroyed 65 to 70% of homes and buildings, killing 14 people.

Teams of nonprofit volunteers visit Dawson Springs for continued recovery work.

Dawson Springs, a town in West Kentucky’s Hopkins County, was hit hard by the 2021 tornadoes. It destroyed 65 to 70% of homes and buildings, killing 14 people.

Teams of nonprofit volunteers visit Dawson Springs for continued recovery work.

Dawson Springs, a town in West Kentucky’s Hopkins County, was hit hard by the 2021 tornadoes. It destroyed 65 to 70% of homes and buildings, killing 14 people.

Dawson Springs, a town in West Kentucky’s Hopkins County, was hit hard by the 2021 tornadoes. It destroyed 65 to 70% of homes and buildings, killing 14 people.