School choice report: Public schools could lose millions if Amendment 2 passes

Published 9:46 am Tuesday, July 16, 2024

- House Majority Caucus Chair Suzanne Miles, R-Owensboro, presents House Bill 2, a proposed constitutional amendment related to education funding, on the House floor Wednesday. (Legislative Research Commission)

Warren County and Bowling Green Independent Schools could lose millions in state public education spending if November’s “school choice” amendment passes, according to a new report.

The Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, a left-leaning research group, analyzed what happened in other states that adopted private school voucher programs around the time Kentucky tried and failed to do so.

Researchers hypothesized that Kentucky’s public schools, particularly rural school districts, will bear the financial brunt of a successful constitutional change this November.

Kentucky’s constitution requires the legislature to “provide for an efficient system of common (public) schools throughout the state.”

It states that the Commonwealth cannot use educational taxpayer funds for nonpublic schools, like private or religious schools, until a majority of Kentucky voters say otherwise in an election.

In November, Kentuckians will decide whether to give the General Assembly the leeway to provide financial support for students outside the public school system.

Proponents of the amendment say that parents deserve more choice in their child’s education, particularly in response to underperforming public schools.

Opponents argue that school choice already exists, and that Amendment two will provide tuition refunds to families that don’t need it while cutting public education funding for those that do.

Report: School choice likely means public education cuts

The KyPolicy report makes a couple of assumptions. Since Amendment two does not detail any specific school choice policies, its goal is to examine the most likely policies.

KyPolicy Executive Director Jason Bailey said that based on past attempted legislation, it’s possible to predict that the legislature will pursue a private school voucher program.

In 2021, the General Assembly passed House Bill 563, which would have created education opportunity accounts in Kentucky.

Under the legislation, nonprofits would gather donations from individuals and groups, who could receive a nearly dollar-for-dollar tax credit for their contributions.

The “account-granting organization” would then allocate funds to parents of eligible students under a certain household income threshold. Students could then use the money for tuition and other educational expenses at a nonpublic school.

The legislation was ultimately struck down by the Kentucky Supreme Court for violating the state constitution.

If the constitutional amendment passes, and the legislature pursues vouchers again, funding will likely be diverted from public schools, Bailey said.

“The options are very few,” he said. “Public education is the largest item in the state budget. Tax increases are not on the table right now. It’s hard to imagine them coming from anywhere else.”

Public school funding generally makes up about 43-45% of General Fund expenditures, although its share has recently been cut to the 37-39% range, according to the report.

This is one of several ways the legislature has signaled a willingness to cut public education funding, the report posits. For example, the legislature has not fully-funded school transportation since 2005, although it came close in the current budget.

If the legislature doesn’t raise taxes or cut public education funding to pay for the hypothetical voucher program, it would have to cut other areas of the budget, like Medicaid, postsecondary education or human services.

How much would school choice cost?

Much of the school choice conversation is a guessing game, since lawmakers did not attach any specific policy or plan to the constitutional amendment.

Nonetheless, the report estimated the cost of a voucher program in Kentucky based on the impact of similar policies in other states.

Many states started with limited eligibility for vouchers, but have loosened or eliminated income-based restrictions in recent years. They include Florida, Arizona, Ohio, North Carolina and Indiana.

Florida spends $4 billion annually on its voucher program, 31% of the amount it spends on public education. Arizona spends $1.1 billion, 16% of its public education budget.

According to KyPolicy’s analysis, if Kentucky were to adopt a Florida-scale model, it would cost an estimated $1.19 billion annually — equal to the salaries of nearly 10,000 public school personnel.

If the commonwealth opted for an Arizona-scale program, it would cost $597 million annually — amounting to nearly 5,000 public school personnel.

Finally, if Kentucky spent just 5% of its public education budget on vouchers, it would cost $199 million annually, a loss of 1,645 public school personnel.

The report also estimated the impact of each model on Kentucky school districts.

Warren County Public Schools would lose 15% of its budget, an estimated $27 million annually, under the Florida model. Under the 5% model, its budget would drop by 3%, a loss of $4.5 million each year.

Bowling Green Independent would lose between $1.6 million and $9.6 million annually, based on the program scale.

Rural districts would generally lose more, since they rely more on state funding. For example, Edmonson County Public Schools would lose an estimated 3% to 18% of its budget depending on the program scale.

Who do vouchers help?

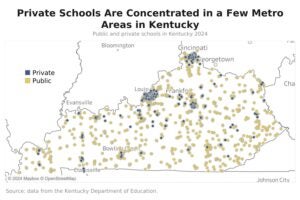

Nearly half of Kentucky counties don’t have an existing private school, and 80% of the state’s private schools are concentrated in 8% of its ZIP codes, the report found.

Outside of the Golden Triangle — Jefferson, Fayette and Kenton counties — private schools are harder to come by.

Dr. Casey Allen, superintendent of Ballard County Public Schools, said those that travel across county lines to attend private school already have the means to pay for transportation and tuition.

He doesn’t see any benefit in his rural community to allowing the state to fund nonpublic schools. Allen also takes issue with a common pro-school choice argument by Kentucky Republicans: What’s wrong with state education funding following the child?

“There is an assumption then that when we lose one student that all of a sudden, all of the expenses in the district are reduced by the proportional percentage that one student means to our district and it’s simply not the case,” Allen said.

Carter County Superintendent Paul Green also emphasized that fixed costs like insurance and transportation remain the same even when there are fewer kids to educate.

“You lose 10 students in a building, well, that’s less than a teacher, but that’s $50,000 to $60,000 in lost revenue,” Green said.

The report authors reviewed current research and found that between 65% to 90% of families receiving vouchers in other states already had children enrolled in private schools, were home schooling or entering Kindergarten.

The voucher amount doesn’t necessarily cover the full cost of tuition, transportation or other educational costs, and for many public school parents, the gap is not closable.

“Vouchers tend to fund those who already have more at the expense of everyone else,” Bailey said.