School choice fueling debate

Published 3:33 pm Friday, August 9, 2024

By SARAH MICHELS, Bowling Green Daily News

This is the first installment of the Daily News’ Educating Kentucky series examining five major issues Kentucky students and schools are facing. Some sources are unnamed to protect their anonymity when speaking about sometimes-contentious issues.

Supporters and opponents of Amendment 2, the so-called school choice amendment that would allow public taxpayer dollars to go to non-public schools, agree on one thing: something needs to change in Kentucky education.

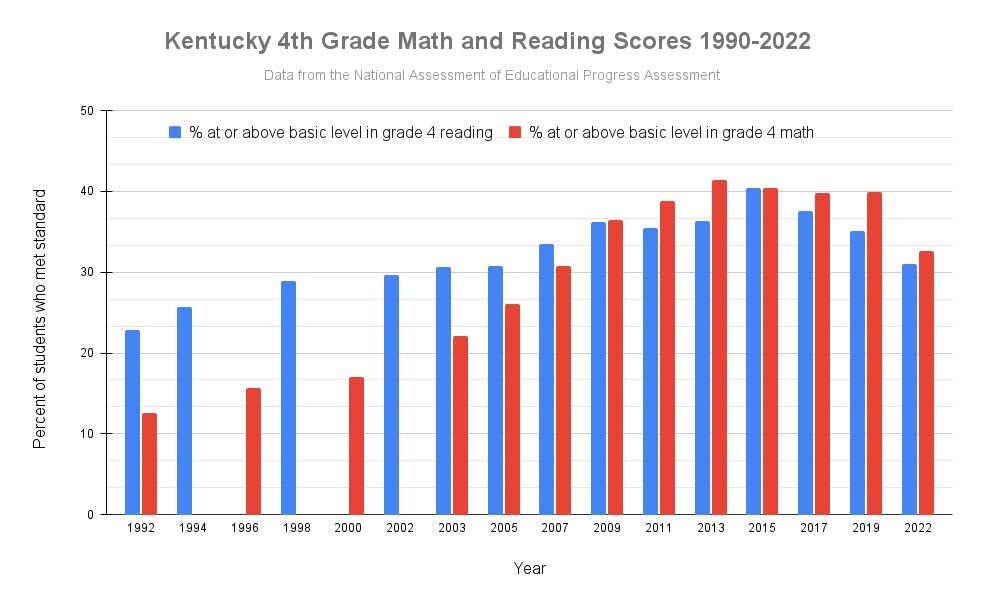

In 2022, 69% of Kentucky’s public school fourth-graders were not proficient in reading, while 79% of eighth-graders failed to reach proficiency in mathematics. This isn’t new; the trend line of Kentucky performance on national education assessments has been declining for about a decade.

Amendment 2 supporters think the solution to poor performance is opening up state coffers to provide parents more choice where they send their kids to school.

Opponents, however, believe that Kentucky public education is underfunded, and restoring funding would solve the issue.

Kentucky’s school choice history

School choice covers an entire spectrum of initiatives.

Kentucky has open enrollment, one form of school choice that allows students who live in one public school district to cross borders to attend school in another district. Those students count toward districts’ daily attendance figure, the core determinator of district funding.

However, the state constitution forbids the use of public tax-dollars for any non-public schools. The Kentucky Supreme Court confirmed this in 2022 when it struck down the legislature’s attempt to create educational opportunity accounts.

Under the proposed law, EOAs were pools of money certain families could use to help pay for educational expenses. Donors could count their contribution toward these accounts as a tax credit.

If Amendment 2 passes, there are several other school choice options.

One is charter schools, non-traditional public schools funded by the state but run independently. They operate under their own rules, outside the purview of the district, and may specialize in areas like STEM or the arts or have smaller class sizes.

Another is private school vouchers, money given to families who meet a given set of criteria to help pay for private school tuition.

During the 2024 General Assembly, opponents of Amendment 2 repeatedly asked what specific policy supporters would pursue if the amendment passes this November. Again and again, they were told that was not relevant to the debate over putting the amendment on the ballot.

They worry about giving the supermajority Republican legislature a “blank check.”

Sen. Matthew Deneen, R-Elizabethtown, told the Daily News that he can’t say what they will do.

“I don’t want to speculate,” he said. “So I think it’s best to take one step at a time.”

Jim Waters, president of conservative think tank Bluegrass Institute for Public Policy Solutions, agreed.

“A lot of the fears can be addressed when we do the legislation down the road, when we have that debate,” Waters said. “And I think we should have a vigorous intense, debate about what is best.”

Who uses school choice?

School choice proponents tout it as a way to lift up disadvantaged kids by giving them an option to flee failing public schools.

Beanie Geoghegan, co-founder of Freedom in Education, helps out at More Grace Christian Academy, a Louisville school that services low-income, minority students with a biblical curriculum.

“When you look at the data of the schools where (More Grace students) attended, you’re looking at reading proficiency scores of 13%, math proficiency at like 6%,” she said. “So because their families don’t have the means to take them out of that setting, that’s what they get. I mean, that’s unfair to trap those students in those schools that aren’t serving their needs.”

However, data from many states with school choice shows that a majority of school choice program participants do not come from public schools.

In Indiana, 69% of those who participated in the state’s educational choice scholarship program during the 2021-22 academic year had never attended an Indiana public school.

In Florida, 13% of 122,000 applicants last year were leaving public schools; 69% were enrolled in private school previously and 18% were kindergartners just entering the system.

In Arizona, just under half of school choice program participants came from public schools.

Daviess County Superintendent Matt Robbins questioned how many kids school choice actually helps, given this data.

“We’re paying part of somebody’s bill,” he said. “This idea that we’re helping a kid in poverty is really just smoke and mirrors.”

Plus, Robbins said, Kentucky’s private schools are concentrated in a few areas: Louisville, Lexington and northern Kentucky. According to a KyPolicy analysis, 63% of Kentucky counties do not have a private school.

“For a kid in a rural area whose closest private school is 30 miles away, it might as well be in Los Angeles,” Robbins said. “Imagine eastern Kentucky with the mountains, like OK, here’s a voucher, hand that to a family in rural Kentucky, and say, ‘Yeah, you got a choice.’ Really, I have a choice? Come on, that’s absolutely ridiculous.”

Geoghegan said it’s a “false assumption” that every private school student comes from a wealthy family.

“I know families who work two and three jobs to be able to pay tuition to a private school, and having that extra little boost for them would maybe allow them to only work one job and send their child to a private school,” she said.

Will public schools lose money?

Amendment 2 detractors say new forms of school choice have the potential to defund already-underfunded public education in Kentucky.

Cloverport Independent Superintendent Keith Haynes said even small departures in his 276-student district could have major impacts on their ability to provide services. If they lose 10 kids, that’s a teacher’s salary, but not enough kids to justify getting rid of a teacher, he said.

A western Kentucky superintendent said districts incur fixed costs, like lighting, heating, cooling and providing supplies no matter how many students they serve.

Dr. John Garen, retired professor of economics at the University of Kentucky, said that’s not looking at the bigger picture.

While public schools lose SEEK per-pupil funding and potentially a portion of their federal free and reduced lunch funding when a student leaves, Garen said there are local, state and federal education dollars that are not distributed on a per-pupil basis. The public school keeps those, despite having one fewer student to teach.

But with high instances of private school and home-schooled students using school choice programs in other states, public school leaders wonder how the state will serve both public school students and a new group of students it has to pay to educate.

“I don’t know where that money’s gonna come from,” one eastern Kentucky superintendent said. “So are we going to raise taxes? Or are we going to have to make cuts in other places to fund this?”

A southcentral Kentucky superintendent echoed those concerns.

“I think if the legislature would boost SEEK to $5,500-$6,000 a kid for every public school, then more power to them if they want to put more money to private school vouchers,” he said. “But I think until they fully fund what we’re trying to do, it seems like it’s not a good avenue right now.”

One Republican lobbyist said the education budget “would absolutely increase.”

“What you’ll pragmatically see is a sustaining and growing public school funding, and then a new pot of funds going to these Education Savings Accounts or other programs,” the lobbyist said.

However, Deneen did not say where specifically funding would likely come from.

“I think the funding for public education and private or charter schools is not a question of this or that; it’s more of this and that,” Deneen said.

Competition and accountability

School choice supporters say it provides much-needed competition for public schools, who will be incentivized to up their game.

Opponents say any competition is on an uneven playing field because private and charter schools are less accountable to the public. Public schools have to publish data publicly that other schools do not, like test scores, demographics and attendance records.

“It’s time that the monopoly of the public school system is sort of given a little bit of competition, that they are encouraged to focus on spending their money in places where student learning is going to be the priority and not any other agenda,” Geoghegan said.

Garen, the economist, said the point is helping students, not the public school system.

“The fundamental question is, are the public schools doing a good job with the funds they have?” he asked. “ … I think the bottom line is that we want students to be able to do well, and if the private schools and charter schools are outperforming, then that ought to be encouraged.”

One central Kentucky superintendent wants to make sure the legislature is using the “same measuring stick” for public, private and home schools.

“If everyone votes yes, my ask would be that we monitor all public, private and home schools with the same assessment so that we see what the impact is of public, private and public schools on the overall student,” she said.

School choice track record in other states

Depending on the measure of success, some states have enjoyed successful school choice programs, while others haven’t. Deneen said it was like “comparing apples and oranges.”

“Some states have seen tremendous increases, sometimes in behavior, sometimes in test scores, some are the same,” he said. “So there’s different data that’s out there that supports either side of this.”

In Arizona and Iowa, for example, education budgets have exponentially increased since school choice was established.

A study of charter schools in 29 states by the Center for Research on Education Outcomes found that 83% of charter school students performed the same as or better than their peers in reading, and 75% performed the same as or better in math.

A compilation of studies reviewed by Ed Choice found mostly, but not all, positive impacts on public school students’ test scores after school choice was implemented.

Robbins said there’s a lot of “partisan data,” but that “objective data” from university studies has found that voucher programs have either a negligible or negative impact on academic achievement.

“To me, that’s why we would look to improve education and change options and spend more money – is to improve student outcomes,” he said. “And if it doesn’t do that, then it’s like, OK, well, why would we even be having this conversation?”