Educating Kentucky: What happens when kids stop coming to school

Published 12:17 pm Wednesday, August 14, 2024

By Sarah Michels, Bowling Green Daily News

This is the third installment of the Daily News’ Educating Kentucky series examining five major issues Kentucky students and schools are facing. Some sources are unnamed to protect their anonymity when speaking about sometimes-contentious issues.

Kentucky kids as young as 14 and 15 are dropping out of school. Well, not technically; they’re not filling out any paperwork.

But when faced with court intervention for truancy or chronic absenteeism, some parents are opting to take their children out of school entirely under the guise of homeschooling, said a west Kentucky district of pupil personnel (DPP) who oversees attendance.

In that DPP’s school district, homeschooled students now outnumber the enrollment of its largest elementary school. Although there are accredited homeschooling programs that allow students to earn their high school diploma, he’s concerned many aren’t utilizing them.

The district is not unique. One southcentral Kentucky superintendent said the number of students being homeschooled has “jumped astronomically since COVID.”

During the 2018-19 school year, there were 70 to 80 kids on his district’s homeschool roster; now, there are 190 students. He said that equates to a $550,000-$600,000 SEEK funding loss each year.

“It’s easier to get up and learn in your pajamas than it is to get up and have to report and things like that,” the superintendent said. “It’s a very attractive and a very easy process in the state of Kentucky to homeschool. The duty to keep records … a lot of times, our staff is spending all their time trying to deal with truancy regarding kids that are enrolled, and I worry about the quality of education that some kids are getting.”

Several school leaders told the Daily News that a rise in homeschooling has been one side effect of the pandemic. It’s part of a broader issue — chronic absenteeism.

Chronic absenteeism: A new pandemic

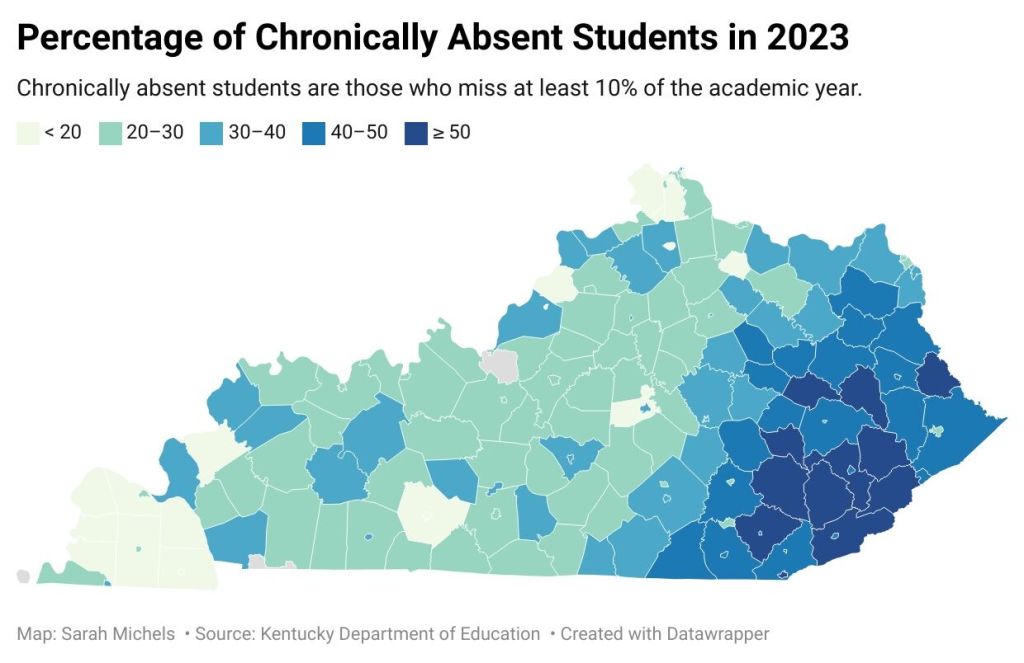

In Kentucky, chronic absenteeism is defined as missing at least 10% of an academic year for any reason. That’s about two days a month.

Statewide, chronic absenteeism has skyrocketed. In 2018, 18% of Kentucky students were considered chronically absent; in 2023, 30% fit the criteria.

The highest rates fall within eastern Kentucky, according to Kentucky Department of Education data.

Research has connected more missed school days with lower standardized test scores and grades, higher drop-out rates, worse job prospects, poorer health and an increased likelihood of getting involved in the criminal justice system.

Anecdotal evidence about the kids going into homeschooling suggests that the problem may be worse than it appears.

Court or vacation: Two groups of chronically absent students

Typically, students who are flagged as truant face the most punitive consequences for chronic absenteeism, like court intervention and home visits.

But several school administrators noted that there is another group of chronically absent students – those who miss just as many days as truant students, but whose absences are technically excused.

“There are situations where parents have learned to work the system, and they know which clinic to go to to get a doctor’s note,” said Cloverport Independent Superintendent Keith Haynes.

Another DPP, who serves a central Kentucky district, said parents will tell them that the best time to travel is when everyone else is in school. “It’s not illegal,” he said. “It only hurts the child.”

“A child that has 15 excused absences is the same as a child that has 15 unexcused absences,” he added. “Neither get anything from the school. They both miss school. The difference is one goes to court and one goes on vacation.”

A doctoral student also working as a Kentucky school counselor said that even those who don’t get in legal trouble face consequences.

“Parents have to understand that what it does to the kid is not only are they behind, but then they start to feel completely deflated because they’re like, ‘Well, I just don’t know what’s going on, I can’t figure this out,’ ” she said. “They start to feel at some point that there’s no use in trying anymore.”

Why are kids (and parents) opting out of school?

During the pandemic, everyone was given a reason not to show up, said one central Kentucky superintendent.

“We got out of our patterns, we got out of our habits, and it’s really hard for people to get back in,” he said.

There’s a “general apathy” among students and parents about attendance, Haynes said.

“Since the pandemic especially, we’ve just seen this sort of notion that it’s not a big deal to not go to school – ‘I just wasn’t feeling it today, so I didn’t come,’ ” he said.

One western Kentucky superintendent said she thinks parents experienced virtual learning alongside their children and came away from it with the wrong message about the value of school and quality of education.

“What we did during COVID was because of a pandemic,” she said. “It’s not best practice, and it’s not what we would typically do in a classroom.”

Virtual learning may have caused parents to feel less strongly about attendance, or pushed them toward homeschooling.

“In their minds, (they think), ‘Oh I could do that,’ but they don’t realize what all they’re missing,” the superintendent said.

Kentucky law requires homeschooling parents to inform their school district’s superintendent of their intent to homeschool, establish a bona fide curriculum and keep attendance records.

Parents are also supposed to record progress in the required subjects – reading, writing, spelling, grammar, history, mathematics, science and civics – in case of inspection by DPPs or the Department of Education.

There are no testing requirements. KDE does not accredit homeschools, and has limited governing power over them.

Several school leaders said check-ins with homeschools often fall through the cracks.

“They don’t come back and take a test, they don’t have to prove that their child has progressed a year, they don’t have to prove they’ve taught anything,” one superintendent said. “Some do, some don’t.”

Impact of absenteeism

Missing school means more than a backlog of homework assignments, said Sen. Matt Deneen, R-Elizabethtown.

“We can’t help someone if they’re not there,” he said. “… Sure, you can take online courses and all those things, and that’s fine. But there’s so much more to education than the test, than the class. It’s about relationships. It’s about dealing with others.”

Average daily attendance is also central to districts’ allotment of state funding.

Several school leaders said this year’s SEEK gain was nearly or completely wiped out by a loss in attendance.

Alongside missed socialization and funding, chronic absenteeism spells trouble for the future economy.

“I hear from business leaders all the time that they can’t get people to show up to work,” one southcentral Kentucky superintendent said. “So as important as it is to teach kids how to read and how to solve equations, it’s really important to also teach them you got to show up every day.”

House Bill 611

The General Assembly attempted to address the issue during the 2024 legislative session. It passed House Bill 611, which requires students who incur 15 unexcused absences to be reported to the county attorney for potential court intervention.

Part of the intervention is a conference with the child and parent, where the attorney may come up with a diversion agreement, a probationary period during which the student cannot miss four more days or they will face stronger court action.

Haynes is thankful the legislature is “giving more teeth” to truancy laws.

“If that had been in place, we would have been filing a lot of charges, quite frankly,” he said.

Daviess County Superintendent Matt Robbins said he thinks it has potential, but could see it also overwhelming courts.

“The volume could become so much that we’re dealing with truancy way too late,” he said. “It needs to be a well-oiled machine and needs to be very efficient. And if it’s not, then it will have little to no impact on a situation.”

Other potential solutions

The doctoral student is planning an intervention in her district. Research has shown her that high levels of family engagement are associated with low chronic absenteeism. Also, poverty is a top indicator of absenteeism.

She wants to work to re-engage kids and parents, potentially by honing in on family education and home visits to share the importance of school and identify barriers, or setting up mentors and daily check ins for chronically absent students.

Other school leaders suggested spending less time criticizing public schools’ faults and instead highlighting their value, providing services like mental health counseling and free meals, taking the extra step to identify what’s wrong, and keeping kids engaged.

“The way to improve attendance is you make kids feel if they don’t come to school, they’re gonna miss something,” one central Kentucky superintendent said. “And if they don’t come to school, they’re gonna be missed.”